To start, let's imagine a normal collision inside your everyday hadron collider. Two beams made of heavy-ions (e.g. lead) going in opposite directions intersect at certain points in your collider (e.g. where your detectors are typically located). These nuclei will have a certain amount of overlap and this is what we call centrality and it is determined by the impact parameter (b), the distance between the center of the two nuclei.

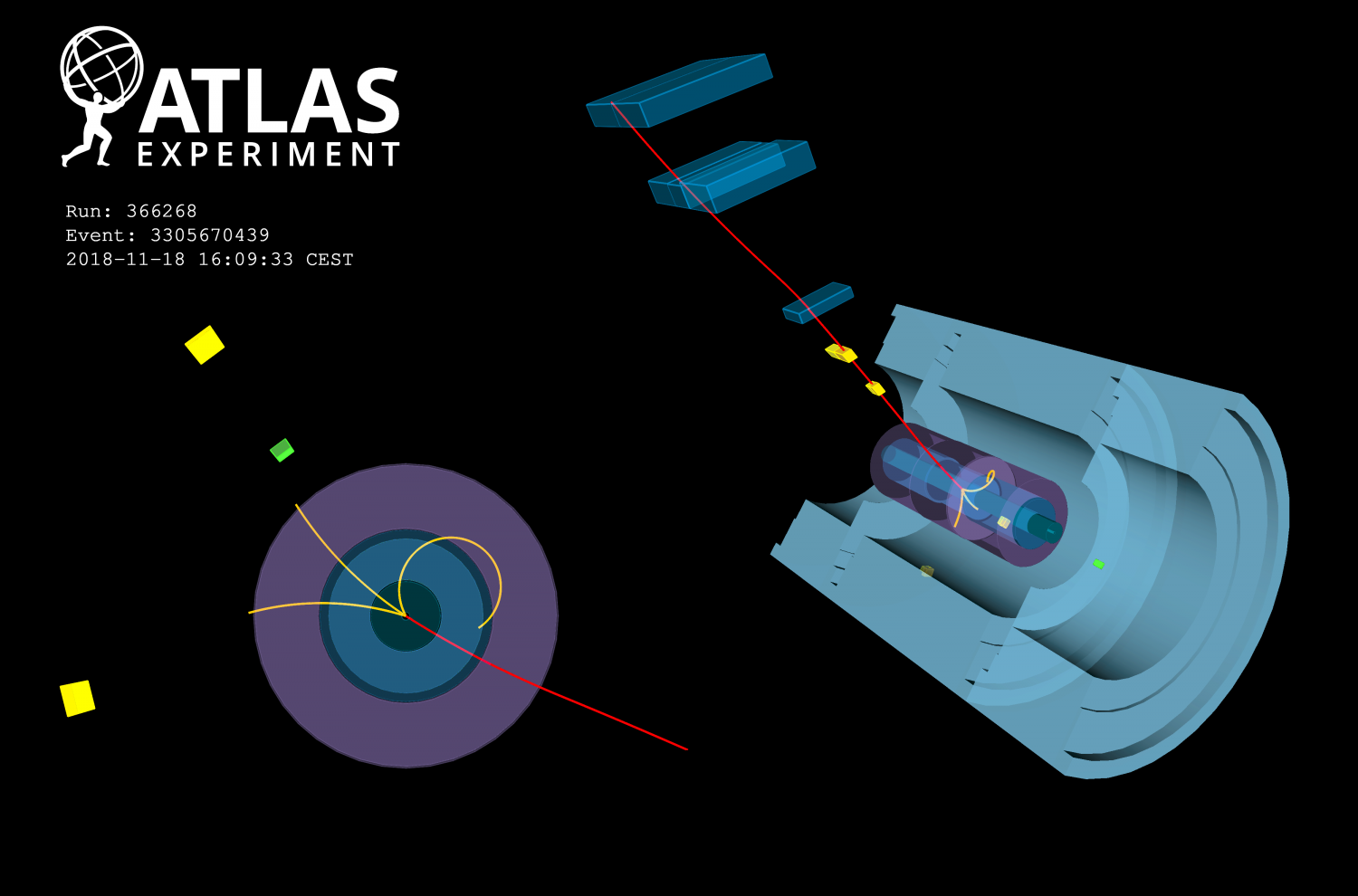

Now this is where UPCs come in, when the two nuclei have a impact parameter greater than the sum the radius of the two nuclei (we treat them like hard shells), the collision is a UPC. This means that UPCs don't involve the nuclei crashing into each other!

A reasonable question comes to mind: "But UPCs have collisions in its name, is something actually colliding?" Yes, there is something actually colliding, Photons!

When these nuclei are accelerated to high speeds (near the speed of light), their electric fields contract in size due to the lorentz force. This increases the strength of the fields, so when two nuclei pass by each other, they emit virtual photons that can interact in a varity of ways:

So can you control how many photons are made and their energies? Yes, we can by increasing the nuclear charge (i.e. using heavier nuclei) which makes more photons. To increase photon energy, we can increase the beam energy (because photon energy increases with Lorentz contraction). However, there are limits to these things due to the accelerators.

"So you use a purpose-built collider to not smash stuff. Why do this in the first place?"

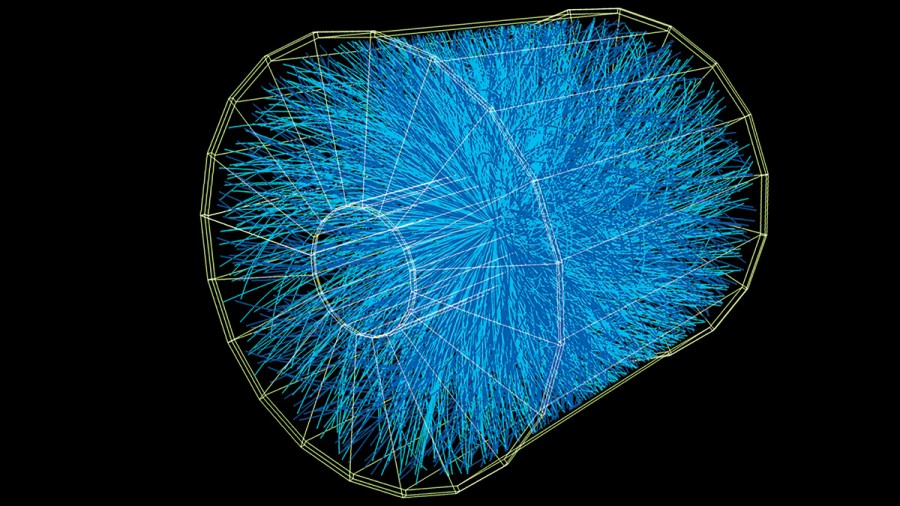

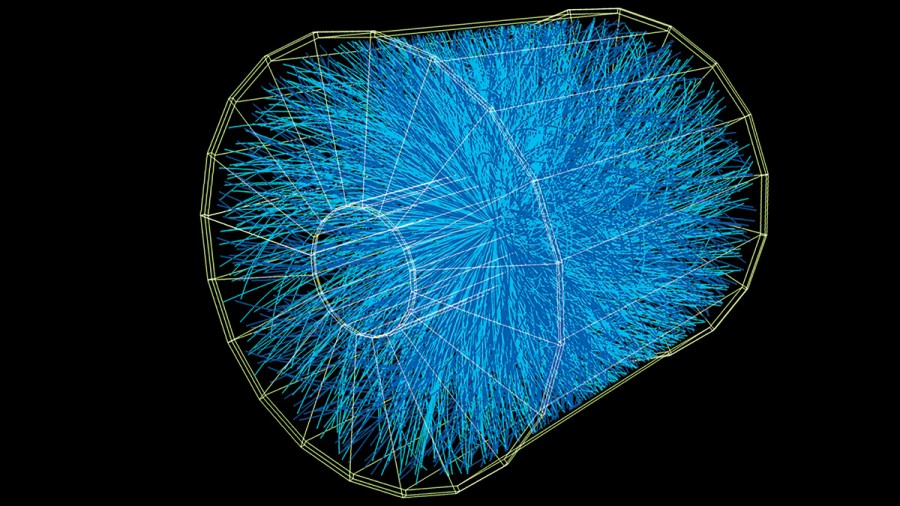

The main advantage of this is when it comes to searching for unique and rare particles and their decays. With your run-of-the-mill heavy-ion collision, these ions are contain lots of matter which sprays particles everywhere. The main challenge of studying high energy collider based physics is how to find what you are looking for. With these heavy-ion collisions, the numerous particles make distinguishing stuff from other stuff difficult (think: needle in a haystack)

Yeah, understandably there is a lot of background stuff which affects accuracy of these measurements, especially with the rare particles. But with UPCs, there isn't all the junk like with a normal heavy-ion collision, so background is very low! This means super precise measurements for these rare and unique particles!